This is the first in a series of essays, in which I will discuss the primary factors that bear on the practical research and engineering work of the machine vision integrator.

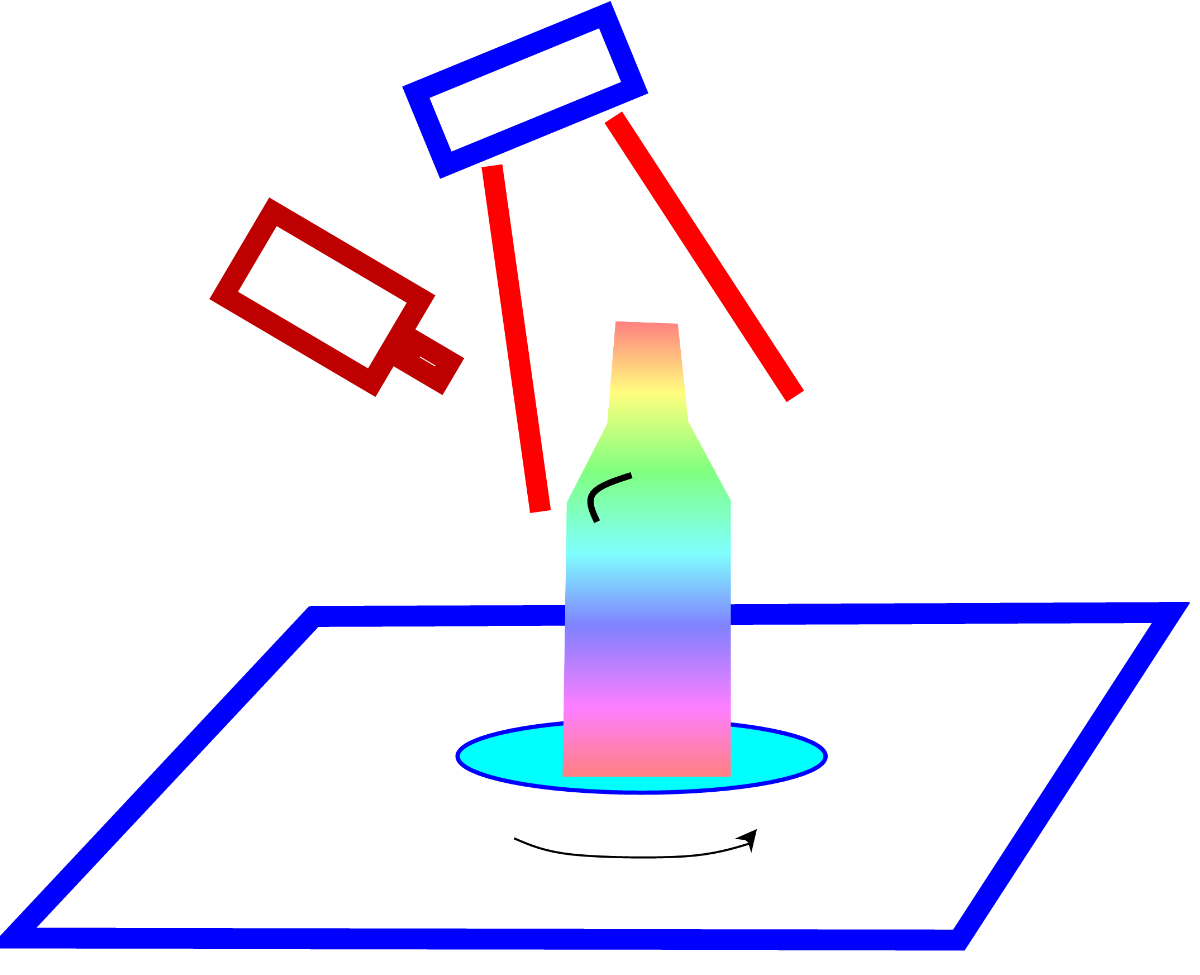

Many people’s first observation of “machine vision” is a tabletop demonstration, possibly at a trade show.

This is the simplest instance of machine vision. But an instrument alone, is not the same thing as a vision machine.

Vision machine development is much more complex. The design of the vision machine is entirely dependent on:

- characteristics of the product to be inspected,

- nature of defects to be detected,

- requirements, constraints and impediments from the factory,

- the degree of human involvement.

Most vision machines are custom designed and built. Some applications are standard, requiring a stand-alone machine (e.g. batch sorting of fasteners). These can use an off-the-shelf sorting machine. However, very many times, the requirements arise from a quality problem in an existing line. This requires the integration of a vision machine into the line, which must be custom developed. Also, many batch-type inspections involve parts requiring unique handling for adequate imaging. This also, must be custom developed.

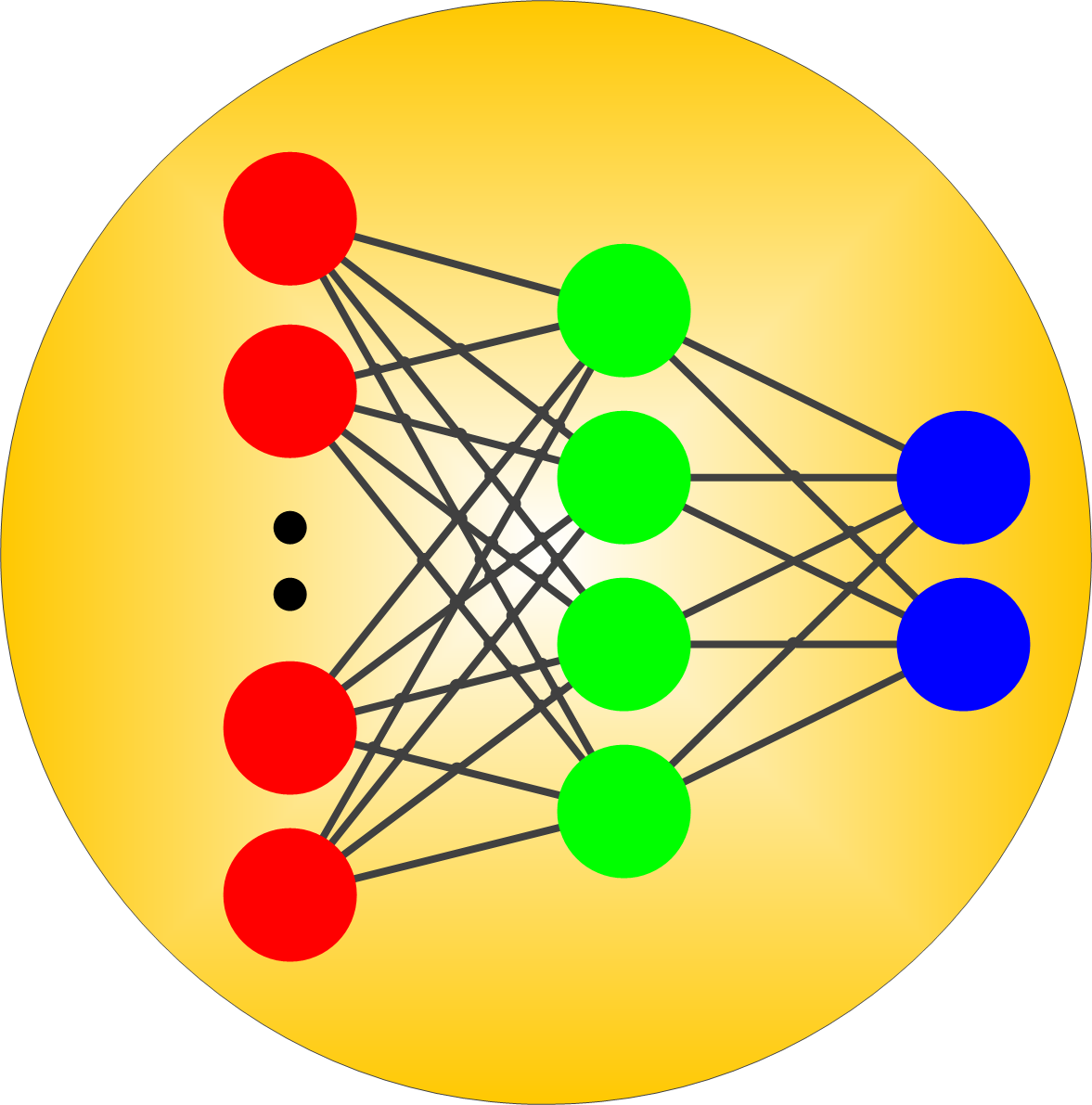

At this point, it is evident that the term “integration” is used in two senses. First, the integration of cameras, lights, computers, image processing libraries. This is selection of off-the-shelf components. The guideline is to use what’s available and not reinvent the wheel. Second, to integrate the vision machine into the factory environment. Here, custom work is usually required for:

- Learning about the particular manufacturing environment.

- Adapting the vision technology to the existing factory.

- Developing an interface for humans and/or factory automation.

- Discovering environmental problems (impediments) and learning how they affect vision and then developing a way to deal with it.

Applications span a range of complexity:

The purpose of this short essay is to address a common misconception among potential users of machine vision, relating to the complexity of the issue.

In fact, machine vision is not a simple as people sometimes think that it is.

In my experience, the principal complexity is not in cameras and lighting. Excellent off-the-shelf products exist, with a wide range of capabilities. The principal complexity in building a vision machine usually has to do with the “Three C’s”: clarity, cleanliness and consistency.

- Clarity refers to clear access of the lighting and camera to the object to be inspected.

- Cleanliness refers to the prevention of environmental contaminants (dust, oil, food bits, shavings, etc.) from obscuring the camera and the object under inspection.

- Consistency refers to the need to position the object under inspection in the same way, from one time to the next.

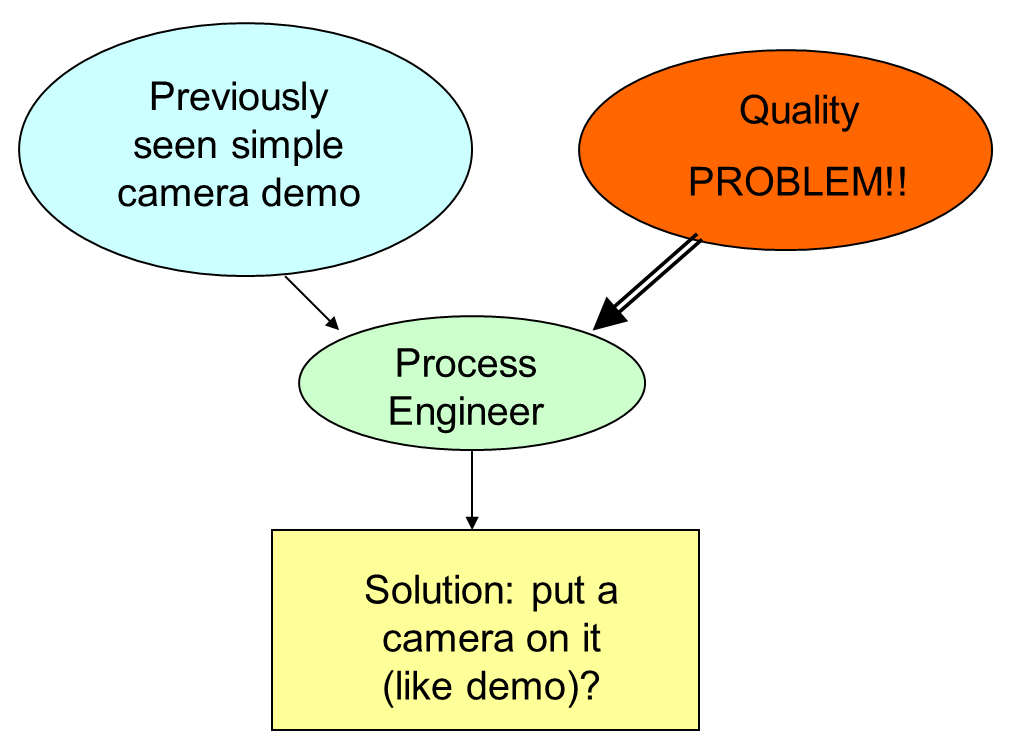

Why is complexity underestimated? With what consequence? Complexity may be underestimated by perception that a simple trade show-type demonstration of an instrument (camera, light) constitutes a meaningful representation of a machine vision solution. This can be schematically represented as follows:

At this point one of three outcomes happens:

- Good fortune smiles and the simple solution works.

- The simple solution does not work, and either the quality problem remains, or

- The problem is solved, with much TIME and MONEY.

But, engineering is not about luck and it’s not about unsatisfactory outcomes.

Systematic vision machine engineering involves the following steps.

- Learn about the application-both inspection and operating environment.

- Conceive of one or more methods.

- Test, first in the lab, then at the factory (if possible).

- Make a mechanical mock-up and test with initial software: address mechanical handling and impediments.

- Design and build the machine.

- Test and make minor refinements.

- Performance testing.

- Documentation.

- Run-off.

- Delivery, installation, training.

- Support.

- Modifications (upgrades over time).

In subsequent essays, I will discuss at some length the key points 1, 3 and 4 from this list.